During the past two decades, the videolaryngoscope (VDL) has become a valuable and effective tool for the management of the airway, not just in the realm of anesthesiology, but also in other medical specialties in clinical scenarios requiring tracheal intubation. In countries such as the United States, this represents over 15 million cases in the operating room and 650,000 outside the OR. The overall accumulated incidence of difficult airway is 6.8% events in routine practice and between 0.1 and 0.3 % of failed intubations, both associated with complications such as desaturation, airway injury, hemodynamic instability and death. In fact that the VDL has been proven improved visualization of the glottis, higher first attempt success rates, and a shortened learning curve, most of the time it is use in a wide range of clinical settings, including the operating room, intensive care units, emergency departments, pediatrics, obstetrics, to consider its routine use.

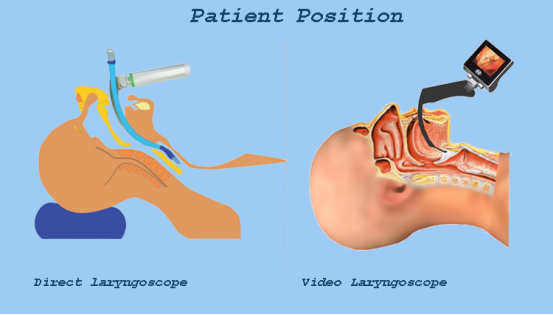

Traditionally, the management of the airway (AW) has been a skill practiced by various medical specialties, but particularly by anesthesiology. Since the development of orotracheal intubation (OTI) direct laryngoscope (DL) has been classically considered the gold standard for most patients. However, negative outcomes in airway management have been reported over time, usually associated with increased morbidity and mortality of patients.(1)

Since the advent of the classical laryngoscopes back in the forties, numerous devices have become available for the management of the AW, including laryngeal masks, bougies, fibrobronchoscopes and videolaryngoscopes. The latter provides significant advantages as compared to DL due to the enhanced visualization of the glottis, minimal cervical manipulation, higher success rates in OTI, reduced learning curve, and the possibility of external assistance during the procedure (Table 1)(2). Consequently, the use of the VDL has become increasingly popular with a growing number of practitioners adopting its use not just in anticipated difficult airway cases or rescue intubation, but in routine practice, giving rise to a new paradigm of whether it may be considered the new standard device for OTI, based on efficacy and safety of the results(3).

Table 1. Videolaryngoscope in the management of the airway.

Advantages | Disadvantages |

No airway axes alignment required | Even with adequate visualization of the glottis, the insertion of the endotracheal tube may be difficult |

Improved glottic view | Costs and availability of the device |

Improved intubation first-attempt success rate | A large number of models available (difficult to standardize) |

Reduced learning curve | Probably longer OTI times |

No cervical mobilization required | Potential limitation to developing/ maintaining skills in the use of the direct laryngoscope |

Possibility for external assistance during the procedure | Two-dimension view with no perception of depth |

Source: Authors, from Chemsian et al.

Using a video laryngoscope offers several benefits compared to a traditional manual laryngoscope.

Video laryngoscopes provide enhanced visualization of airway structures during intubation. The inclusion of a camera and screen allows healthcare professionals to view a real-time magnified image of the larynx and vocal cords, enabling a better view of anatomical landmarks and potential obstructions. This improved visualization can lead to increased first-pass success rates, reducing the need for multiple attempts and minimizing patient discomfort.

Video laryngoscopes can be particularly advantageous in difficult airway management scenarios. They offer a better view of the glottis, making it easier to navigate anatomical variations, limited mouth opening, or situations with poor visualization due to blood, secretions, or edema. This can help in identifying and addressing airway challenges promptly, reducing the risk of complications and improving patient safety.

Video laryngoscopes may be particularly useful in certain patient populations, such as those with restricted neck mobility or suspected cervical spine injuries. The ability to maintain a better alignment of the airway axis during intubation attempts can minimize the potential movement of the cervical spine and reduce the associated risks.

1. Generally speaking, there has been an increase in first-attempt intubation success rates using the VDL, improved visualization of the glottis is achieved, and less hypoxemic events under various clinical scenarios. This may translate into a potential benefit in terms of less airway complications(4)(5).

2. VDLs are more expensive than DLs; however, the VDL is becoming increasingly popular and this growing demand may lead to increased supply with a subsequent price regulation making the device more affordable to institutions, particularly in developing countries.

3. If VDLs were to become the standard of care for the AW, the scientific societies shall then change the algorithms previously published, recommending the use of the VDL not only for anticipated difficult airway cases or rescue intubation, but also specifying the device or the steps to follow in case of a failed videolaryngoscopy.

4. Although the VDL learning curve has been shown to be shorter as compared to other devices for the management of the AW, the limited availability of equipment may result in insufficient training of many practitioners in this area, and consequently in a gap in the development of the necessary skills for the use of this technology.

5. Due to the range of devices available in the market, it is difficult to assess the performance of each type of VDL in different clinical scenarios. This may lead to some uncertainty about to the selection and optimal management of the VDL, depending on the type of patient or clinical situation.

6. The limited availability of VDLs or the lack of training of the practitioners responsible for managing the airway, implies that we should not rule out, limit or lose the skills in the use of other devices for OTI. Therefore, it is critical for the practitioners to maintain their skills in the management of different devices and both continue to improve the access to, and training in the use of the VDL (6)

The VDL has proven to be an effective and safe device for OTI in different clinical scenarios(7) , delivering significant improvements in the visualization of the glottis, successful first-attempt intubation, rescue intubation and anticipated difficult airway situations. Presently, a number of scientific societies have recommended its availability or routine use for all OTIs(8). However, the availability and the price of the device hinder its routine use, even in institutions that enjoy high revenues. This situation may change in the future as a result of globalization, increased supply-demand and the evidence in terms of patient safety; the recommendation for a universal use of the device may transform the VDL into the gold standard for OTI.

(1)

Fourth National Audit Project. Major complications of airway management in the UK: results of the Fourth National Audit Project of the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Difficult Airway Society. Part 1: anaesthesia

TM Cook, N Woodall, C Frerk

Br J Anaesth, 106: 617-631, 2011

(2)

Video-laryngoscopy

R Chemsian, S Bhananker, R Ramaiah

Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci, 4: 35-41, 2014

(3)

Review article: video-laryngoscopy: another tool for difficult intubation or a new paradigm in airway management?

J-B Paolini, F Donati, P Drolet

Can J Anaesth, 60: 184-191, 2013

(4)

Videolaryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy for emergency orotracheal intubation outside the operating room: a systematic review and meta-analysis

N Arulkumaran, J Lowe, R Ions, M Mendoza, V Bennett, MW Dunser

Br J Anaesth, 120: 712-724, 2018

(5)

Videolaryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy for adults undergoing tracheal intubation

J Hansel, AM Rogers, SR Lewis, TM Cook, AF Smith

Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 4: CD011136-CD011136, 2022

(6)

Evolution of videolaryngoscopy in pediatric population

A Gupta, R Sharma, N Gupta

J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol, 37: 14-27, 2021

(7)

Has the time really come for universal videolaryngoscopy?

TM Cook, MF Aziz

Br J Anaesth, 129: 474-477, 2022

(8)

Guidelines for the management of tracheal intubation in critically ill adults

A Higgs, BA McGrath, C Goddard, J Rangasami, G Suntharalingam, R Gale

Br J Anaesth, 120: 323-352, 2018